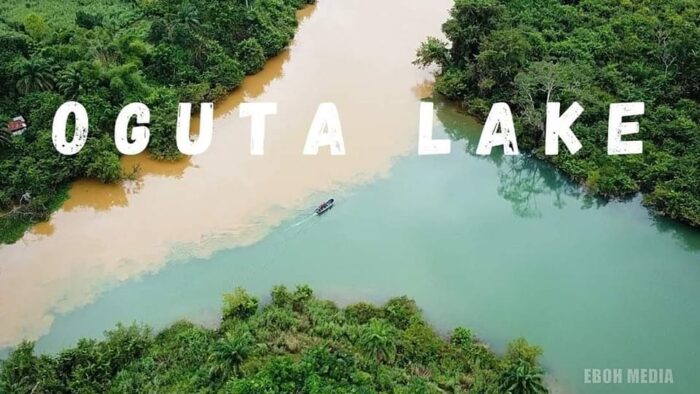

The History Of Oguta Lake and Urashi River (Full Story) – An unseen line separates the greenish blue of Oguta Lake from the murky brown of the Urashi River at their confluence. The two bodies of water meet yet do not mingle, as though bound together by mystical forces. This divide represents the intense tension and marital turmoil between Uhamiri, the lake goddess, and her estranged husband, Okita, the Urashi’s owner, according to local tradition. Where one deity declares the end of its domain, the other begins. Boaters who routinely ferry people and goods across these contested waters make it a point to welcome and praise each deity as they enter their territory; allegiances are offered in exchange for protection and safe passage. Popular wisdom is that it is preferable to respect them from afar than to become entangled in their web.

While this otherworldly power struggle rages on the edges of town, Oguta is unquestionably Uhamiri’s stronghold. The lake goddess, whose name translates to “the shimmer of the waters,” refers to how the essence of her beauty and grandeur is thought to be mirrored in the flashing of light on the water’s surface. She is said to be a woman of incredible beauty and benevolence, and she is in charge of the seasonal tides that feed fields and provide plentiful harvests. She sweetly assists local fisherman by ensuring the lake’s fish supply, but when enraged, she brings death and starvation via floods and plague.

She is Life and Death, Poverty and Prosperity, and, above all, a woman.

Uhamiri looms large over Oguta’s traditional politics. Her multiple identities as a woman and a power figure created a powerful culture of ritualized femininity inside pre-colonial Oguta society, with far-reaching repercussions for indigenous women. She is still associated with concepts of wealth and feminine independence, and her adoration as a goddess gave rise to rites that praised femininity and placed women in crucial governmental positions. Women historically operated and ran the town’s Orie Market; women handled cash and credit transactions, cleaned the grounds, and manned the stalls.

Oguta women have a significant economic and industrial legacy. Up until the early twentieth century, daring Oguta women made a career as long-distance merchants, rowing boats down the rapids of the River Niger to barter exotic commodities in remote markets at Onitsha and Aboh. Many made their name on these perilous voyages, collecting enough riches and status to construct some of the town’s earliest Western-style storeyed structures.

Uhamiri, the source of all riches, is said to reward women who achieve extraordinary success in business. When a woman’s “hands are believed to be good” (an Igbo idiom [aka di ya nma] that means “she produces money quickly”), the locals pay particular attention to her. If her good fortune continues, it is said to be a sign from the goddess urging her to become a worshipper. In response to the vocation, the lady would be admitted to Uhamiri’s inner circle of priestesses and would keep a little pot by her bedside as a sign of her relationship with Uhamiri. Priestesses obtained a monopoly on the ritual activities that kept their community in balance in exchange for observing Uhamiri’s taboos, which included frequent sacrifices and abstinence on the goddess’ holy days, dwarfing menfolk in power and influence. Priestesses were liberated from child-rearing obligations and the jealous, limited gaze of weak men via their devotion to the lake goddess. Their connection with Uhamiri was a marriage in and of itself, and it was possibly the source of Okita’s rage.

Be the first to comment